More about Puerto Rico through the lens of activist-academics Corinne Teed and Dr. Sandy Plácido

To celebrate the upcoming conference in Puerto Rico, we are including an interview conducted by Louise Fisher, Normandale Community College, SGCI Board 2020-2022, for the 2020 conference by Corinne Teed, University of Minnesota, President of Mid America Print Council and Sandy Plácido, Assistant Professor of History, CUNY Queens College, about their work with CEPA. We hope it will keep you excited as we approach 2025.

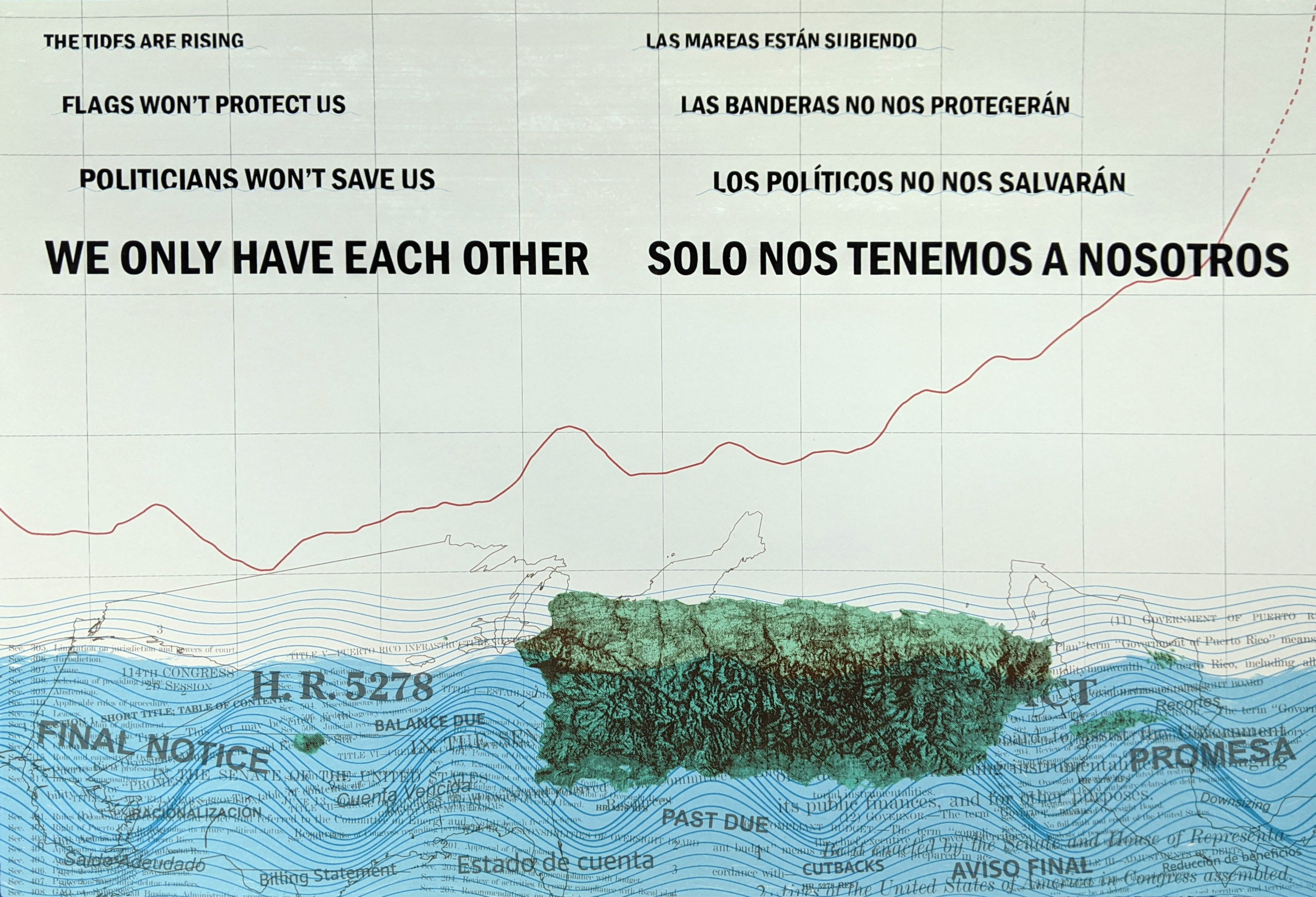

The project and prints featured in this interview are currently part of a fundraising effort for CEPA, an organization based in San Juan raising funds to purchase their QTBIPOC home and community space. You can purchase a print or donate to the fundraiser here: https://givebutter.com/cepa

In this interview, SGCI’s Web Editor Louise Fisher has a conversation with activist-academics Corinne Teed and Dr. Sandy Plácido about their collaborative project Trazando Las Lineas / Tracing the Lines as well as topics of solidarity, cultural understanding, and political action in Puerto Rico and the Caribbean diaspora. The Trazando Las Lineas / Tracing the Lines portfolio exchange was created for exhibit in San Juan as part of the canceled SGCI’s 2020 Puertographico conference.

Corinne Teed is an artist, activist and educator based in Minneapolis, where they are currently an Assistant Professor of Art at the University of Minnesota (Twin Cities). Corinne states, “my origin story in printmaking is related to my history as a community organizer. In Providence, Rhode Island, I was doing a lot of activism around anti-gentrification, immigrant rights, youth organizing and anti-war work.” During this time, they were a member of a worker-owned translation, interpretation and education collective which was comprised of majority Latina members. More of Corinne’s current research and artwork can be found at www.corinneteed.net.

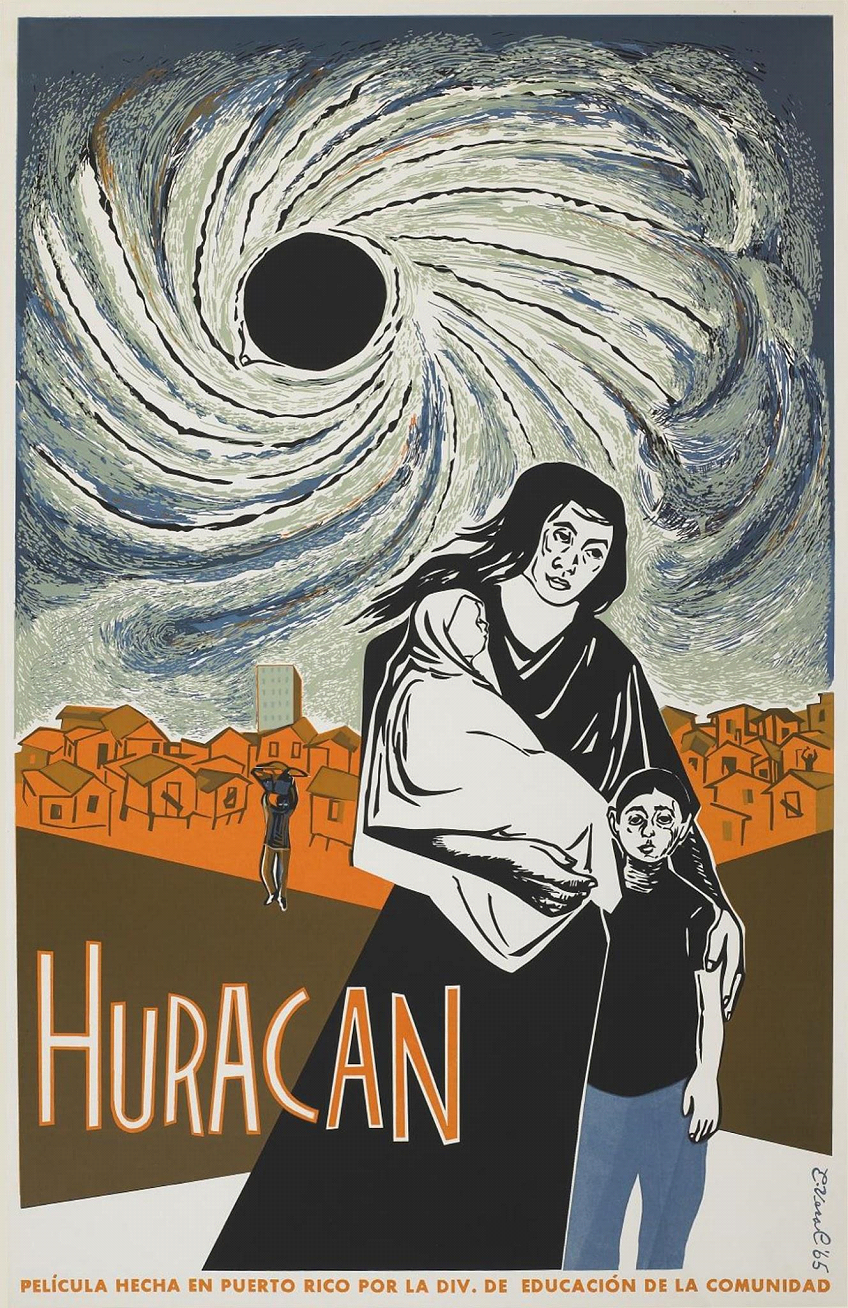

Dr. Sandy Plácido is a historian and activist based in New York, where she is an Assistant Professor of History at Queens College, City University of New York, and the inaugural Dominican Studies Scholar at the CUNY Dominican Studies Institute at The City College of New York. When asked about her research, Sandy says she is “interested in the Caribbean region as a whole as it relates to anti-imperialist social movements.” She has written extensively about the Puerto Rican activist Ana Livia Cordero, who founded El Proyecto Piloto de Trabajo con el Pueblo in Puerto Rico in 1967—a group focused on decolonization which used the arts extensively, especially visual art and silkscreen, in its organizing work.

Louise: How did the two of you meet and ultimately, how did you decide to collaborate?

Sandy: Corinne and I were both visiting professors at Oberlin College during the 2017-2018 year. I was in the History Department there, and Corinne was in the Art Department. I think we met at orientation. I remember I noticed them because you were asking really good questions and making good points. I was like, “this person is smart!” Something I didn’t mention is that I’m Dominican—I grew up in NYC around a lot of Puerto Ricans. A lot of people think I’m Puerto Rican, I’m not—it’s just that I’m close to that community. I’m very much immersed in the Puerto Rican diaspora in NYC. So I think when Corinne and I spoke, Corinne mentioned some of the activism that they had done in Providence with Dominicans and Puerto Ricans. In fact, we have mutual friends who were involved in various movements in Providence. We got on the topic of Corinne’s artmaking, and I mentioned that I know people in Puerto Rico who are very involved, and that I also write about a group of activists who were using art very heavily in the 60’s and still alive. I remember walking down Main Street in Oberlin and I think we decided, “we should do something one day!” And then a year or two later this opportunity came up. We said, “you know what, let’s try to put something together”. So, the idea was the portfolio-—with me being a historian and Corinne being an artist—is that yes, we’re interested in prints themselves, but we’re also interested in these histories of collaboration with Puerto Rican artists and artists in other parts of the world. We really wanted to make a point with this portfolio about histories of solidarity and collaboration across communities that have been impacted by capitalism—in all its many effects.

Corinne: When I saw the call from SGCI, and was starting to think about, “what are ways for on-the-ground collaboration with grassroots organizations”? That whatever we do there could some way support continued activism and community building that’s happening on the island. I called Sandy, and was like, “okay, here’s this thing that’s happening! There’s this conference. This is how these portfolios work. I’m interested in working with you and an organization on the island.” We did a lot of brainstorming. I was actually visiting Oberlin. I can remember the corner I was sitting on while we talked on the phone—standing outside of the restaurant that we always used to go to in that tiny town (laughs). It felt like an easy collaboration because I have the experience of printmaking, and we share a language in the world of organizing, anti-capitalist critique, and decolonizing. So in thinking about how we wanted to structure things was a fun, collaborative process in working on the invites and the proposal for the portfolio. Working with the Center for Embodied Pedagogy and Action (CEPA) has been incredible. I haven’t met them in person yet, but I deeply respect the work that they do and feel grateful that throughout this process we’re going to be supporting them. Part of that support is that we’ll be selling some of the prints afterwards to raise money for some of the work that CEPA’s doing.

Brendan Baylor Print for CEPA

(CEPA’s mission is to foster the decolonization of Puerto Rico, which is an ongoing practice of unlearning and transforming life as we know it. Decolonizing is a healing social justice practice that looks at the root causes of our disconnection with compassion in order to transform trauma into wholeness and liberation.)

Louise: Here is a big question: I’m wondering how conference attendees on an individual or collective level—can contribute to San Juan’s already vibrant community and how can they be an ally to the people there?

Sandy: I follow people on social media, especially on Instagram. I don’t use Twitter as much— but having those day-to-day updates helps. People in Puerto Rico are constantly sharing and writing pieces, producing art, and organizing. They put out calls for funds—they make it known. You don’t have to look that hard to find this very vibrant network of activists. They have web pages and Facebook pages. It’s not even Maria—to really bring my historian into this, right? The economic downtown that happened here in the U.S. in 2008 was already affecting Puerto Ricans years before. We’re talking about a place that’s been dealing with economic austerity measures for—we can safely say close to 20 years—but depending on who you ask, you could also say 120 years since 1898. Since 1952… this is one of those things I find historically with Puerto Ricans, that because they’ve been subject to one of the most—THE MOST—powerful empires in the world, the activist response has been parallel in terms of its sharpness, its level of organization. Puerto Ricans have been organizing forever—intergenerational organizing. So, you can at least start by informing yourself, and following folks. There’s the Center for Investigative Journalism in Puerto Rico, a group of journalists that leaked the “Whatsapp” chat of the governor. There’s also resources like “The Puerto Rican Syllabus”. I always suggest that. It’s an online syllabus put together by a few academics in the diaspora. So even just learning more about Puerto Rican history, finding out about the groups down there. And once you’re in that world, they will let you know what they need a lot of the time. It could be spreading the word, it could be trying to get access to certain resources. There’s one woman I love—Yasmin Hernandez—she’s a visual artist, and she’s one of the diaspora Puerto Ricans who’s rematriated. I love following her and her blog, and her reflections on what it means to come back to Puerto Rico. She’s always saying that it’s not just about money. She pushes people to really think about solidarity. She’s like, “send us good energy! Quit just looking at us.” She pushes the envelope about not just throwing money on the problem, right? It’s also about the kind of political questions we’re asking here, and us thinking about our complicity. There’s so many great groups… And folks there, they’re open to collaborating, but they have gotten a lot of allies reaching out to them so I know sometimes they can get overwhelmed. I think as an ally, you have to think about how you approach groups and individuals so that you’re not necessarily giving them more work. (laughs) We can actually be useful in some way.

Corinne: Last night I was at a talk here in Minneapolis called “Decolonizing Public Art” and the moderator was Candida Gonzalaz who was actually just at CEPA, and they’re a local artist/activist who is part of the Puerto Rican diaspora. The way that they ended the night was asking people to think about questions like: were we not decolonized, what would we wish to see? And what they responded for themself, was to say, and I’m paraphrasing—that they want the return of sweetness—the ways of relating prior to the incursions of capitalism and colonialism. I think that’s something to think about as people coming to another country—participants from SGCI come from many cultures—but one thing that I know about the many cultures of the US is that we can be brusker, we can have a “me first” attitude, we can be impatient. There’s a lot of things that I have learned as a traveler in Latin America that I carry with me. That’s something I think about—how a lot of us relate to our surroundings, to just take a breath and a step back, think about the ways we take up space and share space with others, and what a practice of generosity in that looks like while we’re in San Juan.

Sandy: Yeah, that makes sense. I would just add that people want us to come in with that compassionate witnessing. People are open—they want people to know what it’s like-—but sometimes as travelers you just go to a place and you have your blinders, and you’re not really listening, not really looking. That’s one of the things that frustrates people—like, “these stupid people come in and don’t even pay attention!” (laughs) So, just absorbing, listening—there’s so much happening, and I think people would appreciate that because we do have roles of complicity. People don’t even realize the relationship between Puerto Rico and the US. And we actually do have power, because the US Congress has ultimate control over Puerto Rico. As US voters and US citizens, we have a huge role to play in what’s going on in Puerto Rico given the US jurisdiction over Puerto Rico.

(División de Educación de la Comunidad (DIVEDCO) silkscreen poster, 1965.)

Corinne: I want to add one last thing. I don’t want to speak for you Sandy, but maybe you agree with this. As someone who’s newer to academia, and someone who comes from a history of community organizing—a huge question I have is, “how as people in academia, are we staying connected to community-based work and supporting grassroots organizations that are not as institutionalized as we are?” I am part of an institution and that affects how I approach things and it has its own form of hegemony that’s affecting me, and it’s really important for me to figure out bridges to those lives and not feel like they have to be in conflict with each other. I think that’s one of the questions that I came to this project with, is how as academics—because SGCI is an academically oriented organization and institution—are we questioning the way we engage with grassroots organizing and support it? For many academic institutions can feel elite and alienating and/or also that they suck up resources instead of offering resources back to the community, which particularly as part of a state public institution, we constantly have to question at the University of Minnesota. Always wondering, what are we doing as a public institution? As the art department, how are we relating to surrounding communities? I’m so new here, I’m still figuring that out. But I think that’s a question that we’ve brought to the project too. Or it’s a question that at least, for myself as an academic, I’m always asking myself. And I see Sandy as someone who is asking that question too. Is that accurate?

Sandy: Yeah, absolutely. There’s always been a synergy between my activist work and my academic work. I went to grad school because I thought I could—though my studies—move forward activist movements. My hope is that by digging into the past, it produces further evidence and material that current diasporas can use to move their movements forward. When I was working as an organizer—I did immigrant rights organizing in New York—I remember it was really useful to bring in that academic, historical, theoretical work into the activist spaces because we need to have vocabularies and frameworks for understanding all of these structural issues that helps people feel less alone and isolated. They can see that it’s a structural, ongoing problem and it’s not necessarily because it’s their fault or because they’re bad. The synergy is absolutely there, the institutions make that false divide because it’s in their interest to do so. But I write about activist intellectuals, and I think we need more—we need to bridge that divide more. You really need both. You need to see the big picture in order to do the daily work, otherwise you just get lost. The people in power are really smart, and they have a lot of resources. I’ve always found some of the smartest people I’ve met are organizers, not academics. A lot of us need to learn from them… they tend to be at the vanguard at understanding all the things going on in society. We as academics are trying to catch up, that’s why we do field research and try to pay attention. So the knowledge is there, we just have to uplift it in our institutions of higher learning.